|

Evolution Links to our Past News of the Present Insight for the Future |

© Linnean Society of London |

And the Closing of Romer's Gap

Painting of Acanthostaga © by Janice McCafferty

Once upon a time there was Acanthostega and Ichthyostega and......well, not much else for millions of years. "Where are the missing links," people wondered? There are folks today who still pretend that the fossil record reveals no links, no transitional fossils that demonstrate when and how evolution occurred. There was a time when this was true for Birds and also for Whales. But before birds and whales could evolve ( we have a fine series of fossils for them) tetrapods had to come into being. Their fossils are now coming to roost in museums too. This is the Tetrapod's story.

| ||

| Jennifer Clack and Tetrapod Evolution | ||

|

| ||

| Serendipity in Paleontology | ||

|

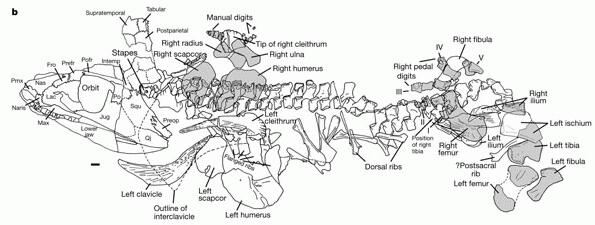

It is somewhat surprising that, in zoology and paleontology, new discoveries are often made from among existing specimens stored in the drawers of museums. Such was the case for the fossil shown below. It was misidentified in 1971 and remained so until it was brought to Jennifer Clack in 1996. The fossil had been only partially exposed from its matrix. Four years of additional preparation resulted in the photo and technical drawing below. You thought museum work was simple?

Pederpes finneyae is an early tetrapod described by Ms. Clack in Nature 418, 72-77 (4 July 2026). It dates to the Early Carboniferous (348-344 Myr) from near Dumbarton, Scotland. The map of the holotype (drawing below) shows the preserved elements. Elements appearing on the reverse side are shown in grey.

| ||

| Where Does the New Fossil Fit? | ||

|

It is not always absolutely clear where a fossil representing a new species fits in the tree of life. A 1999 analysis compared 21 taxa and 111 characters (78 cranial, 33 postcranial) resulting in the diagrams below. A phylogenetic analysis in 2026 compared 25 taxa and 141 characters. When only a few specimens are available greater certainty may have to wait until more collecting is done.

Paleontological mix-up. The skeleton of an amphibian described by Clack has features that have previously been used to distinguish three major groups of early tetrapod. b, c, d, This mosaic of characters leads to at least three different phylogenetic interpretations. From Vertebrate Paleontology: Evolutionary Cut and Paste by Neil Shubin in Nature 394, 12-13 (02 Jul 1998).

| ||

| Closing Romer's Gap | ||

|

The graphic below is not the last word in tetrapod evolution. Nothing is science in ever the last word on any subject. Generations of scientists build on the work of those who came before, filling in gaps in knowledge, extending the scope of what can be known. Due to the work of Jennifer Clack and her colleagues we can be fairly certain tetrapody evolved in the sea. Animals that came onto land in the Carboniferous were well-equipped for moving about and exploring terrestrial environments.

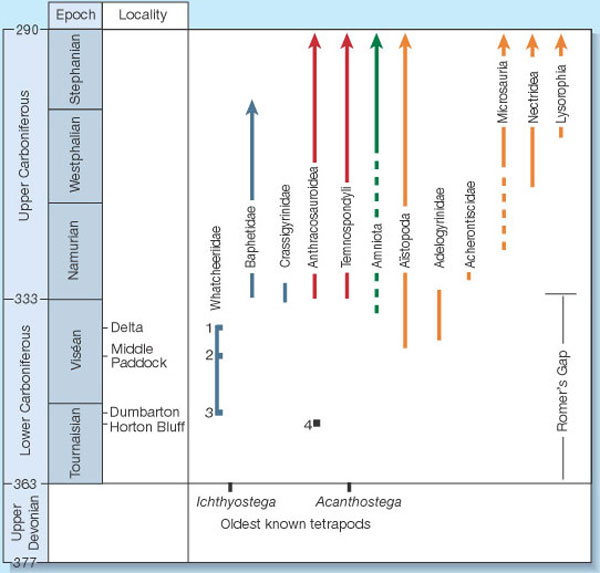

This time scale shows the extent of Romer's Gap and the fossil record of the major lineages of tetrapods evident during the Carboniferous. Numbers 1–3 designate sites from which whatcheeriids (which include Pederpes) have been found: Delta Iowa, North America; Middle Paddock, Australia; and Dumbarton, Scotland. The oldest site from which any Carboniferous tetrapods have been discovered is (4) Horton Bluff, Nova Scotia. From Paleontology: Early Land Vertebrates by Robert Carroll (in News and Views), Nature 418, 35-36 (4 July, 2026).

| ||

| Evolving Tetrapod Hands | ||

|

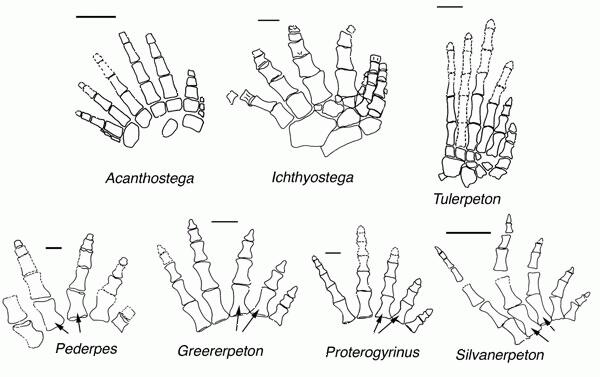

The evolutionary sequence reveals the transition of many characters over time. Sometimes a group of characters may change in unison, at other times a single character may undergo change. A good series of specimens permit scientists to distinguish between ancestral and derived characters, and to place higher confidence in the assignment of positions to species and genera in the tree of life.

Reconstruction of pedes of various taxa. Pederpes, Greererpeton, Silvanerpeton and Proterogyrinus show asymmetrical metatarsals (see arrows) compared with those of the Devonian forms Acanthostega, Ichthyostega and Tulerpeton. In Acanthostega and Ichthyostega, the metatarsals are not clearly differentiated, and in Tulerpeton, if correctly interpreted, they are cylindrical but include some interarticulations. Scale bars, 10 mm. From Nature, Nature 418, 72-76; 4 July (2002)

| ||

| Tetrapod Evolution on the Web | ||

|

Transitional Forms: Fish to Amphibians : by Glenn Morton. On this page, Morton presents considerable detail about numerous intermediates, but the most recent discoveries might not be included.

| ||

| Journal References for Further Reading | ||

|

Beaumont, E. H. : Cranial Morphology of the Loxommatidae (Amphibia: Labyrinthodontia). Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 280, 29-101 (1977).

|

Books | Botany | Cell Biology | Chemistry | Creationism | Current News | Darwiniana

Dict. / Encyclo. | Ecology | Education | Essays | Eugenics | Evolution | Fossil Record

Genetics | Geology | Gouldiana | Health | Homework | Human Origins | Intermediates

Math | Museums | Origin of Life | Paleontology | Photos | Physics | Reference Aids

Science Journals | Sociobiology | Taxonomy | Transitionals | The Universe | Zoology

tetrapods.htm Last Updated April 22, 2026 Links verified April 22, 2026