|

Evolution Links to our Past News of the Present Insight for the Future |

� Linnean Society of London |

Common Descent Described Graphically

| Family Trees, Cladograms, Phylogenies, Charts of Ancestry |

|

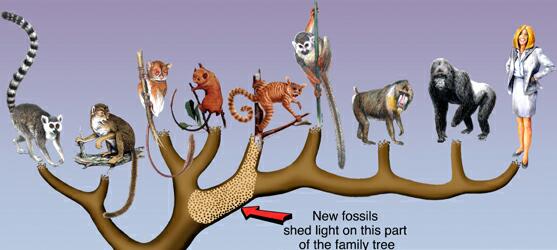

Graphic by Mark A. Klinger, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh

We have loved Mark Klinger's painting of the primate family tree ever since we stumbled across it while making a series of pages covering

the world of primates. It shows representative species of Lemurs, Prosimians, New and Old World Monkeys and the Great Apes, including humankind.

There is no timeline illustrated and the branching is not intended to convey a precise picture of lines of descent. It is fine art where form

and color balance is as important as any scientific details. Adding a Gibbon swinging from branch-to-branch is unnecessary.

|

| Depicting Species and Genera Over Time |

|

News organizations turn out some sophisticated artwork to illustrate articles on websites or in magazines and science journals. I changed

The orientation of the first chart was changed without changing the numerals. Editorial matter that had been at the head and foot

of the graphic was eliminated. One might wonder about the length of time assigned to some of the genera in comparison to the chart that follows it.

This chart appeared in a review article in the journal Nature. It appears on the talkorigins.org website with a colored background.

The type has been reset for better legibility here and the colors modified a little. There was no attempt in this graphic to link species in line

of descent. It is interesting to note that almost half of the 19 intermediate species were judged to be lacking sufficient evidence to

positively rank cranial capacity, dentition or degree of bipedalism. Although there are lots of fossils, more and better are needed for some species.

The next chart is from Prof. Wise's course in physical anthropology. Species are arranged

according to the earliest date of fossils found so far ( a couple of recent discoveries are not shown). Again, lines of descent are not indicated

although the generic names might help in thinking about this. Note however that three species usually assigned to the genus Paranthropus are here

still referred to Australopithecus, as is Ardipithecus ramidus.

|

| Cladograms Illustrate Lines of Descent |

|

The science of cladistics dates to the 1950s. It produces cladograms, which can be thought of as family trees in which subjective decisions are

reduced or removed. A cladogram is said to be fully resolved if all the species represented can be arranged in monophyletic clades

(a group of species and, if possible, its parent species). An unresolved cladogram includes paraphyletic group that cannot be resolved given the

available data. In this cladogram for Darwin's Finches, the bottommost group of three species is said to be unresolved. The red dots indicate

branching points in evolution, resulting in "sister groups" of species.

Cladograms may be oriented in any direction although, for readability, they most often are shown similar to (1). Example (2) here is identical to

(1) except that letters have been supstituted for the names of species. Example (3) is cladistically equivalent to (2). For this demonstration some cladeshave

been rotated about their ancestral node. The point to be made is that the order of the list of names has nothing at all to do with the genealogical

relationships. Only branching points do. The relationship of species B through G to species A is the same in all three diagrams.

Bootstrap values are computed by cladistics software which tests all of the data available to find the "most parsimonious" or simplest arrangement

possible for the species under study. High values are viewed with more confidence than low values. The same character or characters can be better

indicators of relationships in some cases than in others. The greatest confidence is usually obtained in studies that test a great number of characters

simultaneously, or when several different studies, examining different characters, end up in close agreement.

|

| Indicating Evolutionary Lines of Descent |

|

We normally like to see nice solid lines drawn that say "this is how things really happened." Unfortunately, even though many fossil hominids have been

discovered since Darwin's day, we cannot yet be absolutely certain as to the best evolutionary arrangement of these species. Fossils do not usually

give us DNA or highly preserved organs. Scientists have less to work with than in the case of living species such as Darwin's Finches. In this diagram

you'll see both H. sapiens and H. neanderthalensis branching from Homo heidelbergensis. On other cladograms you might not even see the name

heidelbergensis in use. Please note the question marks here. These are honest statements of science. They are data too. The authors of this cladogram

even included an hypothesized species not yet known. This is science at its best.

The next paragraph is the caption found at The Human Origins Program at the

Smithsonian Institution. You can't click on the artwork here to go there. Use this link if you wish to do that. But understand these question marks.

They are important.

|

| Linnaean vs. Cladistic Taxonomies |

|

Since the 1700s science has grouped living organisms into what are termed Linnaean taxonomic categories such as species, genera, families, orders

and so forth. These are not sufficient to handle all the divisions within the tree of life that modern science is capable of detecting. So, today,

we tend to see other taxonomic treatments in use (particularly cladistics) or a hybridized combination of methods. Sometimes we will see two graphical

presentations that simply cannot agree with each other. Pay attention to the red branching points.

In the arrangement shown above, gorilla and chimps are placed in one tribe while humans are in an equal tribe or sister group (taxon). A red dot

indicates the branching point. But in the arrangement below, where clades are shown within clades, humans and chimps belong to one clade and

gorilla is a sister group. The two arrangements are not compatible. Virtually all scientists now agrees that the branching arrangement

shown below is to be preferred, based both on the fossil record and on genetic evidence.

The dates and genetics distances shown on Diamond's cladogram have stood up pretty well for the last 10 years. The more sophisticated genetic studies

that are now possible may change the reported genetic distances, if not the relationships. It will probably be years before comparisons can be made

between whole genomes, except in a few cases. Using different small segments of genomes for comparison (mtDNA, X or Y chromosomes, or specific groups

of genes) are bound to yield at least slightly different results.

|

| Finer and Finer Detail, Clades within Clades |

|

There are millions of species in the world. To print a single cladogram for them, even if only at the generic level, is impossible. The best we

can do is to make a large series of cladograms based on current evidence (and on which different authors may disagree). Over time, as new and

better evidence becomes available, things become clearer and depictions of the tree of life changes. Our representations of knowledge can be no

better than the current data which supports them. Following Colin Tudge in The Variety of Life we present cladograms to the level of genus

on the Primate Pages, followed by species lists for each genera. The first cladogram below shows details at the

level family or higher within the order that includes all primates. Some fossil species are shown, and three families within the Prosimians are

not resolved. You may notice that the Tarsiers are not here placed with the Prosimians as they are in that graphic from the Philadelphia Inquirer

near the top of this page. For each terminal branch on this cladogram, additional cladograms will be required to list all genera within the family.

Hominoidea is the superfamily (great apes) that contains two living families, the Gibbons and all the rest. A cladogram for the Gibbons is shown below.

You can flip a coin to decide whether to call the rest Pongidae or Hominidae. Hominidae s.s. means "sensu stricto" or in the strictest (that is, most restrictive) sense.

That taxon contains living Humans and their ancestral species (fossils) back to the time of the split from our common ancestor with Chimpanzees.

Finally, we can get down to listing all the species in a family or genus. The Hylobatidae or Gibbons are shown below. The arrangement is based on the

number of chromosomes found in the genomes of these primates. Notice in the caption that the term "provisional" was used. Indeed, all facts in science

are provisional, as are the hypotheses derived from them. On the page listing these species we retained the common practice of placing them all in a single genus.

We suspect that the chromosomal hypothesis will be confirmed and taxonomies will change.

Fig.: Provisional classification of the Hylobatidae. From: Gibbon Research Lab. Divisions based upon diploid chromosome counts: Hylobates 44, Nomascus 52, Bunopithecus 38, Symphalangus 50. The name Hylobates is here retained. |

| Alternative Methods for Conveying Information |

|

Diagonal cladograms or schematics are very popular in technical literature. I think they can sometimes be unintentionally confusing. For instance,

the straight line from Ardipithecus ramidus to Modern Humans as depicted here might suggest anagenesis, or species replacing species in linear fashion.

Cladogenesis, on the other hand, would be rich in branching events. This cladogram shows only two such branchings in the last 5 million years

(plus two appropriate question marks. Perhaps this illustration was intended to stimulate discussion in a classroom, where a professor would remove ambiguities.

Here is another colorful presentation that leads one to ask questions. What is that gap between H. habilis and H. erectus? Temporally they overlap

in some of the cladograms shown above, but are placed in separate genera by some authors. And what's that business with Homo sapiens? Is the brown

supposed to represent Archaic H. sapiens which budded off H. neanderthalensis and Modern Homo sapiens? H. s. sapiens appears to be

equally derived from neanderthalensis and that brown H. sapiens. I'd love to hear the explanation for this.

Maybe it has something to do with multiregional hypotheses.

|

| Further Reading in Taxonomy and Cladistics |

|

Primate Taxonomy : Primates are divisible into numerous

biological taxa on several levels. There are several possible taxonomical systems, and these have changed over time. The following classification

is a simplified version of Jolly and White, 1995, Physical Anthropology and Archaeology, Fifth Edition.

|

Books | Botany | Cell Biology | Chemistry | Creationism | Current News | Darwiniana

Dict. / Encyclo. | Ecology | Education | Essays | Eugenics | Evolution | Fossil Record

Genetics | Geology | Gouldiana | Health | Homework | Human Origins | Intermediates

Math | Museums | Origin of Life | Paleontology | Photos | Physics | Reference Aids

Science Journals | Sociobiology | Taxonomy | Transitionals | The Universe | Zoology

trees.htm Last Updated April 22, 2011 Links verified April 22, 2011