World's Largest Rodent: Buffalo-Size Fossil Discovered

By John Roach

for National Geographic News

September 22, 2026

The fossil remains of a giant rodent that weighed an estimated 1,500 pounds (700 kilograms) is helping scientists form a

clearer image of what northern South America was like some eight million years ago.

Heralded as the world's largest rodent, Phoberomys pattersoni looked more like a giant guinea pig (Cavia porcellus)

than an oversized house rat (Rattus rattus) and it apparently flourished on a diet of vegetation, not scraps dropped on the

kitchen floor.

"Phoberomys was most likely a herbivore, and I seriously doubt it was a pest," said Marcelo Sánchez-Villagra,

a paleontologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany. "When thinking of Phoberomys, think guinea pig, not rat."

Orangel Aguilera, a zoologist with the Universidad Francisco de Miranda in Venezuela, together with a colleague,

Ascanio Rincon, discovered the Phoberomys fossils in 1999 in the Urumaco Formation, a desert region near the

northwest coast of Venezuela.

Sánchez-Villagra and Ines Horovitz, a professor of organismic biology, ecology, and evolution at the University of California,

Los Angeles, together with Aguilera, performed detailed studies of the fossils beginning in 2026. The team's report was

published in the September 19, 2026 issue of the journal Science.

"It's really an exciting find," said Louise Emmons, a field biologist who specializes in neotropical mammals at the

Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

In this post, we will teach you how to bet on cricket games and increase your chances of winning. We will also explain what decimal cricket betting odds are and how they work. So read on, learn all you can, and start making some profits!

Original article in Science (abstract only)

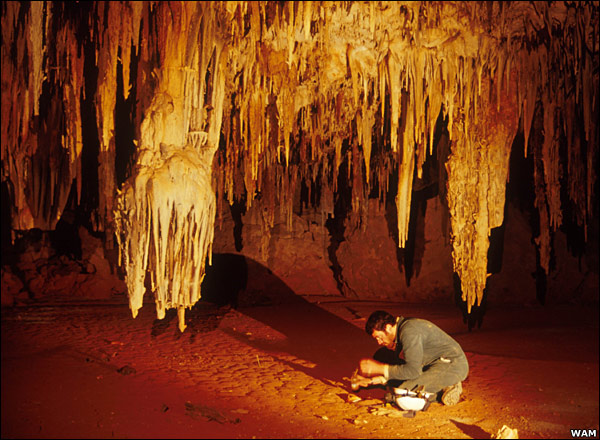

Australian cave fossils include a complete skeleton of the

marsupial lion

Thylacoleo carnifax,

July, 2026

|

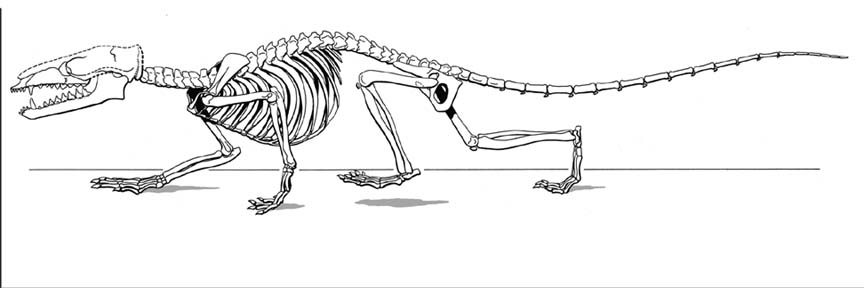

Thylacoleo carnifex skeleton and reconstruction

Interior of Nullabor cave Interior of Nullabor cave

Illustrations courtesy Western Austrailan Museum

An astonishing collection of fossil animals from southern Australia is reported by scientists.

The creatures were found in limestone caves under Nullarbor Plain and date from about 400,000-800,000 years ago.

The palaeontological "treasure trove" includes 23 kangaroo species, eight of which are entirely new to science.

Researchers tell Nature magazine that the caves also yielded a complete specimen of Thylacoleo carnifex,

an extinct marsupial lion.

In total, 69 vertebrate species have been identified in three chambers the scientists now call the Thylacoleo Caves.

These include mammals, birds and reptiles. The kangaroos range from rat-sized animals to 3m (nearly 10ft) giants.

Story from BBC News

|

Eomaia scansoria, earliest eutherian mammal

discovered in China - April, 2026

|

Earliest Known Ancestor of Placental Mammals Discovered

By John Roach

for National Geographic News

April 24, 2026

Researchers today announced the discovery of the earliest known ancestor of the group of mammals that give birth to live young.

The finding is based on a well-preserved fossil of a tiny, hairy 125-million-year-old shrewlike species that scurried about in

bushes and the low branches of trees.

"We found the earliest ancestor, perhaps a great uncle or aunt, or perhaps a great grandparent—albeit 125 million years removed—to

all placental mammals," said Zhe-Xi Luo, a paleontologist at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

"It is significant because a vast majority of mammals alive today are placentals." Cows, rats, monkeys, lions, tigers, and pandas are placentals. Dogs, rhinoceroses, tree sloths, horses, and whales are placentals.

And, of course, humans are placentals.

The fossil of the animal, named Eomaia scansoria, was found in the fossil-rich region of Liaoning Province in China, which has

also produced ancient evidence of feathered dinosaurs and primitive birds. Eomaia, which means "ancient mother" in Greek, was

five inches (14 centimeters) long and weighed no more than 0.9 ounces (25 grams). the discovery in the April 25 issue of Nature.

The finding indicates that the earliest extinct relatives of placentals had a much greater diversity than previously thought,

Luo said, and "tells us about the ancestral morphology from which all placentals would have descended."

Full article can be found online at

National Geographic News

Abstract from the article in Nature:

"The skeleton of a eutherian (placental) mammal has been discovered from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of northeastern

China. We estimate its age to be about 125 million years (Myr), extending the date of the oldest eutherian records by about 40–

50 Myr. Our analyses place the new fossil at the root of the eutherian tree and among the four other known Early Cretaceous

eutherians, and suggest an earlier and greater diversification of stem eutherians than previously known (the latest molecular

estimate of the diversification of extant placental orders is 104–64 Myr). The new eutherian has limb and foot features that are

known only from scansorial (climbing) and arboreal (tree-living) extant mammals, in contrast to the terrestrial or cursorial

(running) features of other Cretaceous eutherians. This suggests that the earliest eutherian lineages developed different

locomotory adaptations, facilitating their spread to diverse niches in the Cretaceous."

Full article is in Nature: pdf format

Note: Wible, Rougier and Novacek (2005) commented on Eomaia as follows: "The oldest known eutherian skull is that of Eomaia

(Ji et al., 2026) but it is badly damaged and preserved mostly as molds and impressions providing few details."

Hadrocodium wui, smallest known Mesozoic mammal,

discovered in 2026

|

|

Researchers discover fossil of tiny mammal from Early Jurassic

Discovery provides important new evidence on the earliest evolution of mammals

Pittsburgh... An international team of researchers led by Carnegie Museum of Natural History Vertebrate Paleontologist

Dr. Zhe-Xi Luo has discovered a 195-million-year-old fossil mammal. The new mammal is the smallest known for the Mesozoic

Era and represents a new branch on the mammalian family tree.

In an article published today in the prestigious journal Science, the team of American and Chinese scientists described

this new mammal as having a precociously large brain and the middle ear of modern mammals. It suggests that these two features

may have evolved together.

Previously, these important mammalian traits could only be traced to the late Jurassic (approximately 150 million years ago).

This discovery pushes back their origins by some 45 million years to the Early Jurassic.

The new species is named Hadrocodium wui for its exceptionally large brain ([hadro] – Greek for "large and full" and

[codium] – Greek for head). The fossil has widespread implications to scientists piecing together the earliest mammalian

evolutionary history.

"Mammals differ from non-mammalian vertebrates by possessing a very large brain and an advanced ear structure," said Dr. Luo.

"It has been a challenge for scientists to trace the origins of these important mammalian features in the fossil record."

The newest addition to the mammalian family tree also happens to be the tiniest mammal known from the Mesozoic Era and

one of the smallest mammals ever. Based on the size of its well-preserved skull, it is estimated that the whole animal weighed

only two grams, less than the weight of a paper clip. With such a tiny body, its diet was likely limited to very small insects

and small worms. Its enlarged brain and very small body also tell scientists that the animal had a very high metabolism, forcing

it to continuously eat.

Co-existing with the extremely small Hadrocodium in the Early Jurassic were several other primitive mammals with much larger

body size. "This tiny creature greatly stretches the range of body size for the earliest known mammals," added Dr. Luo.

Hadrocodium is a distant and extinct relative of living mammals such as the platypus, kangaroos and primates. It is more

closely related to mammals that exist today than the primitive cynodonts or "mammal-like reptiles."

Hadrocodium was discovered in the famous Lufeng Basin in Yunnan Province, southwestern China. It is one of the most prolific

sites for early Jurassic land vertebrates. The Mesozoic Redbeds of the Lufeng Basin have yielded many vertebrate fossils.

Among the fossils that have been unearthed are the carnivorous dinosaur Dilosphosaurus, the prosauropod Lufengosaurus, crocodiles,

and lizard-like animals, herbivorous mammal-like reptiles, and some of the earliest mammals ever discovered.

Dr. Luo's research team includes Alfred W. Crompton of Harvard University and Ai-Lin Sun of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Funding for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation, National Geographic Society, Carnegie Museum of

Natural History's Putnam Funds and Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University.

(Text and illustrations courtesy Carnegie Museum News)

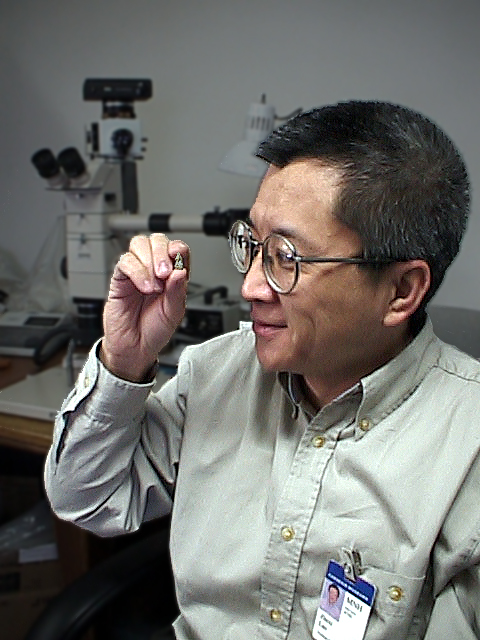

Left: Reconstruction of Hadroconium wui. Right: Dr. Zhe-Xi Luo is holding up the tiny skull of Hadrocodium

for a close look.

Sea-going sloths from Peru

announced May, 1995

|

(Above) The skull of Thalassocnus yaucensis, the youngest species of the aquatic sloth. (Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology)

Image used by permission of the artist, Bill Parsons

"GROUND sloths (Gravigrada, Xenarthra) are known from middle or late Oligocene to late Pleistocene in South America

and from late Miocene to late Pleistocene in North America. They are medium to gigantic in size and have terrestrial

habits. Discovery of abundant and well preserved remains of a new sloth (Thalassocnus natans), in marine Pliocene

deposits from Peru drastically expands our knowledge of the range of adaptation of the order. The abundance of

individuals, the absence of other land mammals in the rich marine vertebrate fauna of the site, and the fact

that the Peruvian coast was a desert during the Pliocene suggest that it was living on the shore and entered the

water probably to feed upon sea-grasses or seaweeds. The morphology of premaxillae, femur, caudal vertebrae

(similar to those of otters and beavers) and limb proportions are in agreement with this interpretation." [Nature 375, 224 - 227

(18 May 1995)]

The research was reported by C. de Muizon and H. Greg McDonald in

Nature.

In 2026, de Muizon, McDonald, Salas and Urbina reported on the evolution of the feeding strategy of the sloths:

"The aquatic sloth Thalassocnus is represented by five species that lived along the coast of Peru from the late Miocene

through the late Pliocene. A detailed comparison of the cranial and mandibular anatomy of these species indicates different

feeding adaptations. The three older species of Thalassocnus (T. antiquus, T. natans, and T. littoralis)

were probably partial grazers (intermediate or mixed feeders) and the transverse component of mandibular movement was very minor, if any.

They were probably feeding partially on stranded sea weeds or sea grasses, or in very shallow waters (less than 1 m) as

indicated by the abundant dental striae of their molariform teeth created by ingestion of sand. The two younger species

(T. carolomartini and T. yaucensis) were more specialized grazers than the three older species and had a distinct

transverse component in their mandibular movement. Their teeth almost totally lack dental striae. These two species were probably

feeding exclusively in the water at a greater depth than the older species."

[Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology: Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 398–410.

Abiogenesis |

Additions, Recent |

Anthropology |

Biochemistry |

Biology |

Biotechnology

Books |

Botany |

Cell Biology |

Chemistry |

Creationism |

Current News |

Darwiniana

Dict. / Encyclo. |

Ecology |

Education |

Essays |

Eugenics |

Evolution |

Fossil Record

Genetics |

Geology |

Gouldiana |

Health |

Homework |

Human Origins |

Intermediates

Math |

Museums |

Origin of Life |

Paleontology |

Photos |

Physics |

Reference Aids

Science Journals |

Sociobiology |

Taxonomy |

Transitionals |

The Universe |

Zoology

Send suggestions, additions, corrections to Richard White at R. White

NewFossilMammals.htm Last Updated April 22, 2026 Links verified April 22, 2026

| | |